Meet Your Author Series started in 2021 when I hosted Botho Lejowa from Botswana. Below is a transcribed account by Daniel Amanya of our conversation held on 1st August 2021 on Instagram live.

Racheal Kizza (Racheal): Hey. Botho, thank you for being here. Good to have you.

Botho Lejowa (Botho): Good to be here. I’m so excited for you. I’m so glad to be the first one.

Racheal: I’m so glad that you said yes. Thank you for allowing to dive in with me.

Botho: I’m so excited. Let’s do it!

Racheal: How have you been? How is Botswana? How are you?

Botho: I am so tired. I think this corona thing has us emotionally, mentally spent. I don’t know if you know, but we’re like the worst, I don’t know in the world, people are dying. It’s so bad. Emotionally, people are not okay. But we’re hopeful.

Racheal: I’m at the point where you are as well. We have been in a 42-day lockdown. It just ended on Friday, and everyone was just ready to leave the house. Once the president gave the green light, we were all like, “Yes, yes, yes! We’re leaving.”

I’m happy that we can have this. Books have done so much for me throughout the lockdown, just being able to get lost in a good book and forget what’s happening.

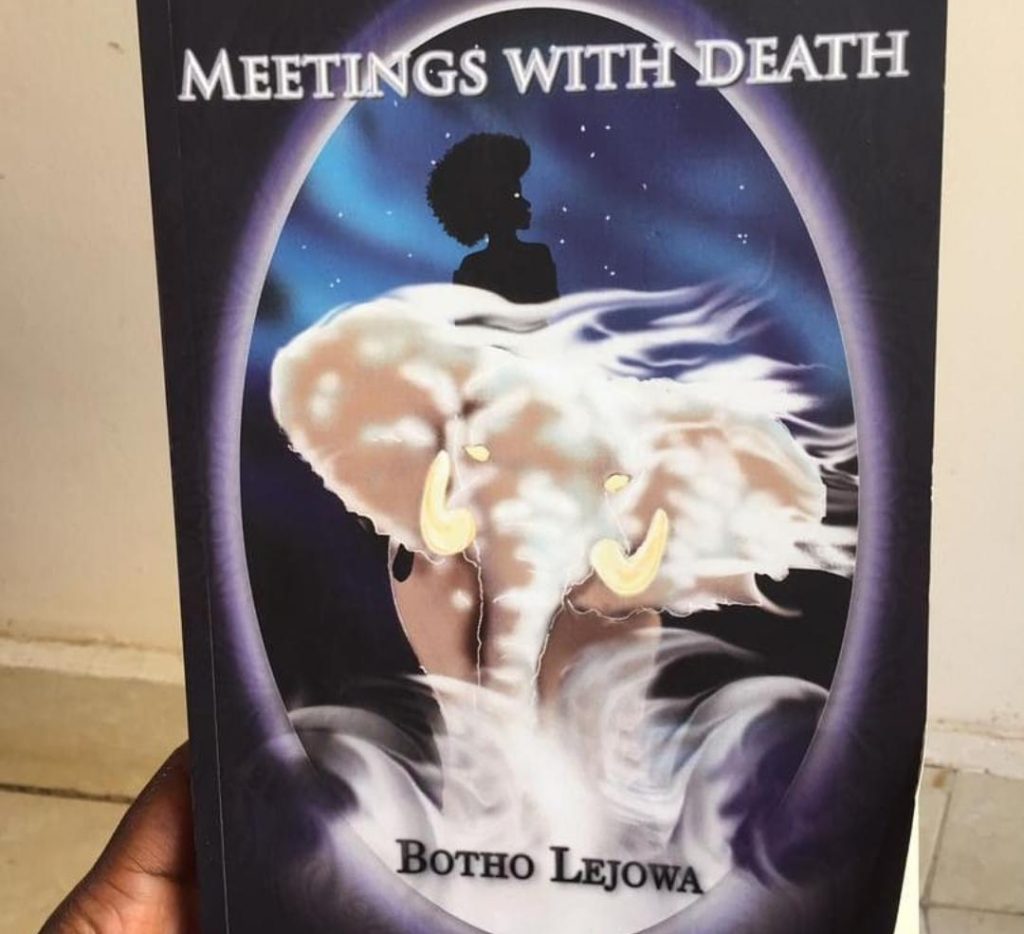

So for our readers, my name is Racheal. I’m a blogger. I love to read, and I love to have book-ish conversations like the one we’re having now. Today, it’s my first IG live, happy new month even, and it’s good that Botho agreed to have this conversation with me. She agreed to be my first guest for the Meet the Author Series that I’ll be running every other month. Today, we’ll be talking about her book, Meetings with Death, a book that I’ve fallen in love with. I’ve read it twice.

Botho, just introduce yourself. Tell our audience who you are, and then we’ll pick it up from there.

Botho: Hi, everybody. So I’m Botho Lejowa. I’m a writer. Meetings with Death is my second novel. I write in the fantasy fiction genre. I’m from Botswana. I’m a big nerd and I love books.

Racheal: I think you’ve said the most important thing, that you’re a writer; because our series is geared around that, me introducing my audience to writers I have encountered over time. And I want to focus on the writers on the continent because I feel like we know all the writers outside the continent, but we don’t know the writers on the continent. So it’s important to get to know the writers on the continent who are doing amazing things. And I was like, why not start with Botho? Everyone needs to read Meetings with Death.

Botho: Thank you. I’m glad you’re diving into your passion like this. It’s amazing, I love it. Were you nervous because I’ve been nervous all day?

Racheal: You remember the last time we did a trial at my office, it wasn’t working, and then I spoke with a friend, Elijah, who works at Ibua Journal, and he agreed to host me at Ibua, and here we are, and everything is working fine. So shout out to the guys at Ibua. Thank you for agreeing to host me.

Botho: Shout out to them.

Racheal: Let’s just dive into the conversation. With Meeting with Death, one of the things that stood out for me is the fact that you give death a face. You make death so vivid that one wonders why. Death is an occurrence. It’s something that we just think about when it has happened, but we don’t think about it as a person. And then in the novel, you make it a person. You make him a person. Death is a person.

Let’s start from there. Why did you give death a face?

Botho: You know what? I don’t know if other writers go through this, but the story writes itself. I don’t really have much of a say in it. I just sit down and write and then I’m shocked as everybody else who will read it eventually. I’m just like what the hell just happened? But what’s sticking with me was the character death. It’s something that we all go through so often in our lives. We lose people that we know and stuff like that, and death is quite vilified.

We’re like death is evil. It’s robbed us of this great person that we know, and I think the thing about writers is that we cope by writing, and it’s an escape form of coping, escapism. I cope with death by writing about it. And I was like, what if death was a person? All these people in the whole entire world hated death, but what if he had feelings too? That’s how that happened. I was like maybe he’s just doing his job.

I cope with death by writing about it. And I was like, what if death was a person? All these people in the whole entire world hated death, but what if he had feelings? Maybe he’s just doing his job.

-Botho Lejowa

Racheal: I had never thought about it that way. Like death is fulfilling his path in life. I love how you say that death and life are like husband and wife. They give each other balance, one cannot exist without the other. When I was speaking with my friend, Elijah, about the book, he mentioned something very interesting. He said that death is portrayed as a man and life is portrayed as a woman. Meaning that in everyday life, the woman gives life—I don’t want to say the man takes it—

[laughter]

Did you think about that when you were writing about death and life? I love the way you described life and how beautiful she is. And the flowery dress and everything going on in the book. I love that. So did you think about it and say, I’m going to make life a woman and death a man, because as we know the patriarchy is continuously taking while the woman is continuously giving and giving and giving?

Botho: You know, I’d like to claim that I’m that profound. I like to just take it and say, listen, yes. Actually, that was the thought process, but I didn’t even think about it. How my characters come to me, they just are. I really don’t have much say in how they are. So yes, I guess it’s just how I view things. If I had to personify life, I would give it a female gender, and she would be beautiful and terrifying all at once, and she would be like nature.

I do parallels between life and nature so much because it’s so beautiful. You wake up and the sun rises just amazing and then the sunset as well, the flowers, a soft breeze. And then at the same time, she’s capable of much destruction. She can really be tsunamis, volcano eruptions, storms, hurricanes, all of those things I think that just encompass femininity. We’re beautiful, give life, but don’t play with us.

And then also, if I had to think about death, I would think -a guy. I don’t know why I thought a guy, but it just felt right to make death a guy.

I do parallels between life and nature so much because it’s so beautiful… And then at the same time, she’s capable of much destruction… tsunamis, volcano eruptions, storms, hurricanes, all of those things. I think that just encompasses femininity. We’re beautiful, give life, but don’t play with us.

-Botha Lejowa

I really liked the evolution of the characters as well because men are sometimes so vilified as well. They’re really made out to be monsters. Obviously, the patriarchy, don’t get me started on that, is problematic. But also I just wanted to highlight the potential for softness, for caring, that guys have. He’s death, but he’s riding for Eana hard. And that’s his person.

I think in all of my characters, I want all of the characters all the time never to be one-dimensional. There’s so many facets to being a human, to being a woman, to being a man, to being black, to being alive, one’s sexuality, all of those things.

Racheal: Someone says that I think in every place in the world, in most cultures, death is personalized as a man and life as a woman.

Botho: Yeah. That feels natural.

Racheal: Like you said it was natural for you to think about death as a man because they are continuously taking and taking, but then also you wanted your character not to be one-dimensional because I like that death wasn’t one-dimensional. When he grows soft for Eana, I was just like what? I was very disturbed by that. Why is death falling in love with Eana?

I like what you say that you didn’t want your character to be one-dimensional and you wanted us to think about death as something more than something we vilify and embrace and think about death as something more. I couldn’t stop thinking about death as a person.

My second question is about modernity and tradition. In the book, you keep drawing a parallel between the two, and I want to understand, do you think that the two can co-exist?

Botho: Yeah, definitely. I feel like we tend to want to chuck away the traditional aspects of our lives I don’t know to what end. I guess we feel like if we’re evolving, then we have to chuck away the traditions, especially things that we don’t understand. I guess so. There’s some traditions that might be archaic and also might be a bit oppressive, but there’s also some things that we should hold on to. But it’s totally up to the person. I don’t think they have to be mutually exclusive.

In the book, I was saying, people are spiritual. I think generally we are spiritual, but it doesn’t mean that being spiritual has to be only in the Christian sense. And why can’t they copy this and why can’t you believe in God and also believe in the ancestors and the way that our ancestors have been living for eons.

I really feel like they don’t have to be mutually exclusive. I don’t want to go too deep in, in case people haven’t read the book and I’m spoiling it. I don’t think they have to be mutually exclusive.

Racheal: You touched on something I wanted us to really focus on during the discussion, that’s African spirituality. Your book is so deep into that that I thought to myself, there’s no way anyone can write such a book without being spiritual or believing in something. I’ll give so many instances in the book and then we’ll just dive into that, because you’ve said that African spirituality, people can believe in God and believe also in the ancestors. And let us focus on that. We know what believing in God means, but what does believing in ancestors mean?

Botho: It’s so different for every individual human being, but I believe that a God exists. There is a higher power. I believe that God exists. I tend to stay a little bit away from the Christian sense of it, but I think it’s maybe the religion that gives me pause because religion is so restrictive, and you have to do this, this, and this. But that’s in my experience. But I believe that there is God. God exists, and the whole point of God is to love people. And if you love somebody, you’re kind to them and you don’t want to be mean. You don’t want to cause them harm.

I believe that people die and in that sense, they become ancestors by virtue of having been dead. So if there’s a spiritual realm, then they’re there also helping God in whatever God needs to be done. So in the sense of Christianity where you’re looking at there being angels, I feel like ancestors are part of that. I think that’s one of the other things I wanted to show with my book that you don’t have to let go of something that has made up so much of your history or your life. You can just put it all together and still be a good person. The whole point of being a human being and being alive is not to be an asshole. I think that’s what it’s all about. Just allow people to do what they need to do, but also don’t chip away at yourself just to fit into a particular box.

Racheal: That’s quite an interesting perspective. When you were speaking, what came to mind is Jesus being an ancestor.

Botho: Yeah, he was alive.

[laughter]

Racheal: Interesting! Elijah in the comment section says, ` the way you capture death is similar to the way Markus Zusak treated death in his book, The Book Thief. ‘ Very interesting.

Botho: Do you know, I have The Book Thief on my bookshelf, and I haven’t read it yet.

Racheal: I guess now is the time to read it and find out if what Elijah is saying is right so you can see the correlation between your book and his book.

Still on African spirituality, like I said I’ll give you instances in the book where you really go in and try to show us that, look, African spirituality can co-exist with whatever else we have. One, you mentioned the becoming, where for Eana to tap into her powers, she has to go through this ceremony, the becoming, for her to become and fully evolve and manage her powers.

Two, was the spirit animals. Everyone had a spirit animal. The book cover was brilliant. The first time I saw the book cover, I wondered why is there an elephant on the book. Why do we have an elephant there? So when I read the book, I’m like oh, the spirit animal. Makes sense. The two, the becoming and the spirit animal, reminded me of the Holy Spirit and how for Christians to be fully activated, you need the Holy Spirit to guide you and simply have a relationship, walk with Him, and do all that you have to do as a Christian with Him guiding you.

And so the becoming and the spirit animal took me back to that, and I was just like, very interesting.

Botho: I don’t have that insight at all. I think with the spirit animals specifically, they are something that people have been writing about for quite some time now. It’s an interesting idea. If you look at some people, you can draw parallels with certain animals. You’re like, oh, this one acts like this animal, those characteristics, and you’re just like, yeah. What if that is their true manifestation of themselves, who they really are?

If you look at Eana’s spirit animal in the book, it’s an elephant, and elephants are very gentle, very loving, and very nurturing. They’re emotional creatures. But also when they get mad, they are destructive as hell, which is pretty much Eana’s story. She’s quiet, she’s gentle, and then people put her in these positions and she’s explosive with her powers.

If you look at Eana’s spirit animal in the book, it’s an elephant, and elephants are very gentle, very loving, and very nurturing. They’re emotional creatures. But also when they get mad, they are destructive as well, which is pretty much Eana’s story.

-Botho Lejowa

I think it would be really cool, like how cool would it be if people were just walking around with their spirit animals and you could see that they’re like, ah, I need to stay away from this reptile. So that would be cool.

Racheal: That would be interesting. I know as well in the Bible, they have spiritual eyes that when they’re opened, you’re able to see things. I think you drew heavily on the Christianity aspect of it without even knowing it, like you said. And so you pulled me into the African spirituality, and I was just like, wow. Did you really think this up?

Botho: I was saying that isn’t it interesting how similar they are? I think with all types of religion and things like that, it’s amazing to me how similar they are. I like the similarities more than having to point out the differences. I think that more often, we’d realize just basically we’re all the same.

Racheal: And then the other bit, still on African spirituality, was Eana’s mum, Thando and the fact that the whole time, we were encountering her in the book, she was in Botswana, but her body was in Zimbabwe, South Africa, the ancestral home. When I got to that part in the book, I was just like, no!!

Botho: You need to say sparingly because there might be people who haven’t read the thing yet.

Racheal: I remember, I had a conversation with Goretti, and we were talking about that part in the book, and she just said, “That is brilliant.” It was so brilliant that I couldn’t wait to have a conversation with you to simply find out, how did you get to that point? I know that at the start, you said that a story writes itself, but did you at any one point think about Eana’s mum in particular and decide I’m going to do this with Eana’s mum or it just unfolded and you realized, oh, wait, Eana’s mum is a clone?

Botho: I really envy writers who are able to plot things out. They’re like this is what’s going to happen, this character has these powers. This is what they know. This is what they do. This is how their character evolves. I really envy that. I wish I was able to write like that, but I can’t. So what happens is I usually just hear some conversations in my head between two characters, and then I start writing. The story, literally, I get shocked as well. I’m like, “Whoa, what is that?” That is some crazy stuff. But yeah, I didn’t plan it out, and I think Thando is one of my favourite characters. She is a badass. I love her.

Racheal: I loved her. I loved her because at the beginning of the book, you set us out with her being so gentle, very calm, and then as you progressed further in the book, we get to see different layers of her. For me, it just reminded me of so many of us as women how we have so many layers to us that the Racheal that some people might know is not the Racheal who is doing this or that, but they’re all facets of one Racheal.

So even with Thando, you do that with her. At the end of the book, we see a strong character who has evolved. From the start, she was actually a strong character. We just didn’t see it. And there were also very many limits to her. She didn’t want to allow herself to be who she really is. And then also the bit about African heritage where, when the mother is trying to shield Eana from knowing who she is, knowing what she is capable of until her best friend tells her ask your mother, and then Eana is just like, what do you mean, ask my mother? My mother has nothing to do with any of this. And then things unfold.

Let’s just talk about the need for us to appreciate and come into our African heritage as you do it in the book.

Botho: I’ll talk about the African heritage part, but then let me just talk about Eana’s mum, Thando. I like what you say she was always strong. We just didn’t see it in the beginning, and that is so true for all of us. We just actually don’t know how strong we are until we have to be; until we’re put in a position where we have to actually survive and get some things done. And then you do the things and you’re just like, oh, I can do that. And then you keep pushing because you feel like anybody can do that because you did it.

But also with Eana and her mum, with Botlhale saying ask your mum and Eana just looking like, what, it’s that thing that so many of us go through where we see our parents as one-dimensional. We see our parents as our parents. That’s it. That’s my mum. That’s it. That’s is her whole entire identification in the world. She’s my mother. But then you’ve missed the fact that they’re emotional creatures as well who’ve had lives before you arrived, who’ve had experiences, all of these things. They’ve lived. They have lived in the same way that you are living.

So Eana has to reconfigure her brain into seeing her mother as more than just this person who’s my mother only. And I think all of us struggle with that. And then we also struggle with how we address our anger to our parents because you can’t talk back to your parent. You get smacked. I think that the relationship between Eana and Thando is so very African. Like how do you get mad at your mother?

So one thing is your mother is more than just your mother and a person in their own right.

Racheal: I think that’s very powerful. Until you mentioned it, I had not thought about the fact that I think about my mother as my mother. Like she’s mummy. Every other thing does not matter—she’s my mother.

But we also think about our fathers as daddy, that’s it, and mummy, that’s their entire role, yet they have so many facets to them, the emotional things. They run businesses. They have interests and desires. We never think about it. We’ve just boxed them up into mummy. That’s who you are. You’re mummy. So I understand Eana when every time they told her that the mum is one of the most powerful shaman, she’s like, what? Really.

Botho: She’s like, you have it wrong. That’s just mum.

Racheal: I think one of the other things I wanted us to fully dive into is still on African spirituality and African heritage because I know you want us to appreciate our African heritage and our African spirituality. But when you were writing the book, did you have concerns about how Christians would perceive the book or you didn’t even think about that? Because I think it could get you a bit uncomfortable if you are a reader and a Christian and you’re trying to think, should I really embrace what she’s telling me to? What about what I believe? Did you ever struggle with that? Did you receive feedback on that from Christian friends who were a little concerned about what you’re trying to get them to believe?

Botho: I haven’t actually gotten anything from anybody yet. And the good thing about it is that it’s fictional. People need to just calm down a little bit and understand that it’s also fiction. All of it is fiction. Obviously, not everybody can do what the characters in the book do.

And basically, it’s just about being open-minded. Like if you read a book in any instance really and wanted to connect with the characters or to feel what the characters are feeling, you have to be able to empathize. Basically empathizing is about just putting yourself in another person’s shoes. And it doesn’t mean that you have to become that person because you’ve put yourself in their shoes. It’s just understanding from their perspective their motivations and what they’re going through and empathizing with it. That doesn’t mean that you have to abandon who you are and your beliefs at all.

You just have to have some introspection as well and be like, cool, that’s cool.

If you read a book in any instance really and wanted to connect with the characters or to feel what the characters are feeling, you have to be able to empathize. Basically empathizing is about just putting yourself in another person’s shoes. And it doesn’t mean that you have to become that person because you’ve put yourself in their shoes. It’s just understanding from their perspective their motivations and what they’re going through and empathizing with it. That doesn’t mean that you have to abandon who you are and your beliefs at all.

-Botho Lejowa

I think human beings are evolving beings. You are not the same person that you were two seconds ago. You’ve got new information, you’ve processed it, and you’ve come to a decision in whatever way that you come to that decision. And that decision is mostly based on your lived experience, how open-minded you are, and stuff like that.

So when I was writing it, I didn’t have that thing that, oh my Gosh, Christians are going to read this and they’re going to tar and feather me. I didn’t have that. I didn’t even think about it because it’s fictional, and I just had to believe that generally as human beings, we’re able to empathize with things that are not things that we might believe in, but we understand that people do. And it makes for a really good story.

Racheal: I like that because I know fiction does that. If you read widely, you get to a place where you empathize. You empathize with people and believe that I don’t believe what you’re saying, but I get where you’re coming from. Like you said, it’s fiction, so it makes for a good story because some of the things in the book had me like, wow. Okay. I don’t know what you’re talking about, but it’s happening in the book, so, all right, we can go with that.

In the book, I noticed that you went with character plotting. Was that limiting in a way, because we have the power of the story alone?

Botho: I think I tend to write like that. I don’t know if I’ve ever tried to write in any other way, but that comes most naturally to me. I look at a character, and I focus on that character’s story. And I feel like it just gives me- I’m more able to connect and to show, to write better so that the reader can connect as well. So maybe I’m just generally an emotional being.

Racheal: An emotional writer.

Botho: And you get invested. From a character perspective, you’re like, oh my God, I’m with this girl. And then things happen, and you’re looking like, oh my gosh, no, no. Also from just my writing, generally speaking, I’m self-taught in that way. I didn’t go to school for creative writing and stuff like that. I was just a big nerd who liked to read and then eventually I started writing.

Like I said earlier, I envy people who are able to plot things out and they’re like, okay, this is what’s going to happen. This character is this. I just write the story, and then I go back and fix it. But generally speaking, the story writes itself and I really have not much say.

Racheal: All right. That’s very interesting. I was in a space with Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi this year, and she said that for her, she plots out everything. Every character she’s going to gauge and put every character there, describe them, what they’re going to do, their age, what they look like, and we were all just like, wow. And then she had just released The First Woman, and we were thinking, you did that for every character in The First Woman?

Botho: That is amazing. When I teach people about writing, I tell them to plot. I tell them to do all of those things, because how I do it isn’t teachable. So I tell them to plot, who is this person, how would they respond. But I think for me, it’s more intuitive. I just know who the character is. And I just remember exactly what they did. And also because I’ve never had 900,000 characters in one book, so I don’t have to keep track.

Racheal: You got us into your writing process. So let’s just get into that. What was it like writing this book? When I was discussing it with my friend, Elijah, earlier he wanted to know, where did this story come from? How did you get to Meetings with Death? How did you get to the title? How did you get to the book itself?

Botho: It’s so weird. I guess when we were talking earlier, I told you that I’d hear like a conversation. Like please, people, please don’t be calling my mums to take me to the mental institution, I beg. So I’ll like hear a conversation in my head and that’s how I build my characters. I’ll hear them talk. It’s so weird.

My best friend once said to me, “Bo, don’t tell people this. They’ll take you the mental institution.” But I hear them in my head. I’ll start writing the conversations, and it’s not yet a story. And with me writing the conversations, I’ll get to know the characters because then I’ll start to see them, picture them in my head.

Again, writers, some of us, write to cope. I guess that’s what I do. People die, and we’ve all had experiences with people close to us dying. You just kind of wonder, in the fantasy world, what if it was like this? And then you’re basically escaping into this world that you’re creating and it feels a little bit better and then also hectically way worse.

Again, writers, some of us, write to cope. I guess that’s what I do. People die, and we’ve all had experiences with people close to us dying. You just kind of wonder, in the fantasy world, what if it was like this? And then you’re basically escaping into this world that you’re creating and it feels a little bit better and then also hectically way worse.

-Botho Lejowa

But it was basically about a girl experiencing those premonition-like situations that so many people in my culture go through. You’ll trip and fall and you never trip and fall, and they’ll be like, ah, you know, that’s like a premonition. Something bad is going to happen. We just take it for granted. It’s just in passing conversation. We’ll be like, oh, no. I dreamt about this. I dreamt of this relative who died then and then we’re just like, that basically means something is coming, something is happening.

And so I feel like Africans generally are very tapped into their spiritual selves. I don’t have experience with being a sangoma. A sangoma basically is an enyanga-type thing. I don’t have experience with that because I’ve never had the calling and I’ve never gone through those rituals, but there are people who have. Maybe if they read the book, they’ll be like, this is so off. This is completely off, but I don’t know.

But I was just saying if we were a little bit more tapped into our spirituality to a point where it felt real, then what would that look like? And that’s how the book really started. It wasn’t so much about death. It was about Eana experiencing these premonitions, and then the world built itself around that.

Racheal: I know you mentioned that you worked with two editors that I know very well, Otieno from Kenya and Crystal Rutangye, a Ugandan editor. What was the process like? Because I know you said there was a lot of back and forth. Do you think it’s really important for a writer to have an editor on board when writing a book?

Botho: Yes. It’s so important. I don’t have that plotting structure situation going on. So I’ll write the story, and I’ll keep editing and editing. So when I worked with Otieno, I think I had edited it like a good, I don’t know how many times. It was a lot. But he was so instrumental in me fixing things that I didn’t see because I was so involved in it. To have somebody who has that eye, reading it and then asking you critical questions, then you get to answer those questions by fixing plot holes that you didn’t know were there.

For example, he’d be like, okay, these two characters just appear at this point, but they’re very integral at this point and onwards. But are they? And I was like, oh, okay. Yeah, actually. So I then changed the beginning to include them, and it just flowed so much better. So from Otieno’s perspective, he’s a structural editor.

So from his perspective, he’s looking to see if there’s a good flow. If everything makes sense. And you’ve been in this story for so long and you as a writer know exactly what’s going on. You might not necessarily be putting it out or you might be leaving out information that helps the reader to get to know how you know. And so that’s what that was about.

And it was hard for me because having to think about- so he’d ask questions. That’s basically what he did. He’s like, okay, tell me more about this. And with me having to answer, then I could see where the holes were, and then I’d have to be creative on demand in fixing the whole manuscript and making sure it was fine. I was losing my mind. I don’t know how many times I told my mum and my friends that I don’t want to do this anymore. Who the F did I think I was? I’m here telling people I can write. Now they want to be creative on demand. What is this? Why is this torturing me? It was really hectic, but I really appreciate it so much that I will definitely be calling Oti again if I write another one. I’ll be like, hey, so I’m ready for the structural edit. Put me through it again.

Crystal was doing the copyediting part of it, so just making sure that the language was okay, all of those things, the expressions and stuff like that. And it was just so many times because she needs to read it once, edit, and then I fix what I need to fix, and she reads it again, and then maybe she’s missed or I’ve missed some stuff. So we kept doing that whole dance. Also, Crystal put me on the wringer. And then there were times where I felt like there’s a creative expression gap between us maybe because of the geographical thing. There were things that I was adamant that I am not changing this, and she was adamant that it needs to be changed. But it was a creative expression thing.

Generally, it was such a great experience. When I say it’s completely different from my first book, I feel like I definitely arrived with this one. I am a writer.

Racheal: I agree. I haven’t read your first book, Leah: A Seer’s Legend. I was excited about reading this because I knew how much work you had put in, but also knowing that you’re working with Oti and Crystal, I couldn’t wait to see what the work was going to be like. And when I read it, I was just like, the language is so beautiful. It’s done so well. The editing is top-notch. Obviously, I would sing Crystal and Oti’s praises.

Botho: Oti is my hero.

Racheal: Writing is so beautiful, your language. It’s so simple. You’re not trying to please us with words. I appreciated the language, that you’re not trying to please us. You’re just giving us who you are, your personality. I could feel it through some of the characters. I think because I’ve met you before. So I could see bits of you in some of those characters. Like, oh, I see her littered all over this.

Botho: Wait, which characters?

Racheal: I think little Eana. I think there’s a bit of you in Eana. And then I know, if Racheal is still on the call, I know that when we met last year, you were closed in on Day 1, and then Day 2 till the end, you’re just blooming, and it was beautiful to watch, it was beautiful to encounter that other side of you, which I saw in Eana.

Botho: It’s because you were feeding us good food, then I was like, okay, these are my people.

Racheal: As we come to the end of the live session, tell us a bit about how the book came to be.

Botho: I don’t know how many people know about the AWT thing, but basically you guys were hosting a workshop, a fellowship programme for writers for a publishing programme. And I applied and I got in, and you flew me to Kampala, and I was so happy. That was a good time. The food, oh Lord, the food. It was so good. And then when I was in Kampala, we went through this programme, and it was a week-long, and it was absolutely eye-opening, like the most fun I’ve had.

I think I’d never been around a group of writers in that way. So it felt like being around people who were like me. It was a great feeling. I think that’s where the bloom came from because I remember telling ma, “These people are like me. They write.” It’s such a lonely experience being a writer because you’re just doing your own thing there, but then having people around you who can empathize with you when you say this character is doing my head in, because they know what you’re talking about. They’ve experienced it. It was so beautiful.

So after the programme ended, we were given an opportunity to apply for seed funding for our own publishing project. And I had Meetings with Death written, and I had the manuscript. I had been on the editing scene of it for quite a while. And so I applied with the intention to self-publish Meetings with Death. And I won it. I didn’t think I was going to win. I literally thought that Rachael was going to win it. I was so certain. I was like, Rachael, this is yours. Like, have you read Rachael’s stuff? Like, Kunda, Adavera. Listen when I tell you that woman can write. So I was like she was going to win it. And then I won it, and then I got sick because I couldn’t believe it.

I had to have a plan on what I was going to use the money for, and a big chunk of it went to editing. I was like I just want to experience this writing thing and publishing thing with an editor who was there. And I’m not sorry. I would do it again. So every time I write, I’ll be calling Oti. Oti will be so sick of me. I’ll be calling him telling him that I’m writing another one. Please, I need your eye.

Racheal: Rachael says she’s proud of you (in the comment section). Just for clarity, the Rachael they were talking about is not me, but Rachael A.Z. Mutabingwa, and she’s writing a third novel.

Botho, as we wrap up, will there be a sequel, because I know we’ve talked about it. After I read the book, I just go to Botho. I was like Botho, where is the sequel to this book? I want it now. I want it. What happened to these characters, that character? What happens to them?

Botho: Otieno, while he was editing, he was like, “Botho, I really think this has potential to be a great trilogy. So let’s edit it in that way that we’re planning for a trilogy.” It’s so weird having to work with somebody else on your creative process because generally speaking, I just write. I don’t plan. But now here he is making me plan, and I’m just like, oh, man, I hate it. How could he do this to me? This is the worst. But then he’s amazing because the writing that I do because of his constant questioning and nudging and stuff like that is great.

I don’t know if I’ll write another because I’m also so over it. With the editing process, I had to read this thing like 900,000 times. So we’re rereading about Eana and death. So I’m a little bit tired of them right now, but maybe I’ll do a thing. Hopefully, this one does so well that somebody is like, yes, write it. Here’s the money. Write it, then I can do it.

Racheal: I really hope so. As we close, just tell the audience, where can they get the book. Where can they get Meetings with Death?

Botho: So it’s on all the Amazon platforms including Kindle, if you’re an eBook person. It’s on Smashwords. It’s on all the Amazon platforms if you’re in Botswana you can also get it at Exclusive Books. That’s where it is. If you’ve read it on Kindle, please leave me a review so that other people can buy it.

Racheal: That’s important.

All right, Botho. It’s been lovely having you. Thank you for agreeing to do this with me. I loved the book, and I hope that people will go out and read it. And please when you do, let me know what you think about the book. I loved it, but I would love to hear what other people reading the book think. I’ll tag Botho when I share the live so that you could follow her and just let her know what you think about her book. I think the affirmation is important.

Thank you joining and being with us. Shout out to the people at Ibua.

Botho: Thank you, guys. Thank you, Racheal. This was so much fun.

Book links

Meetings With Death Book Links: Amazon || Smashwords || Scribd

Leah: A Seer’s Legend Book Links: Amazon

Where to find Botho:

Where to find Racheal: