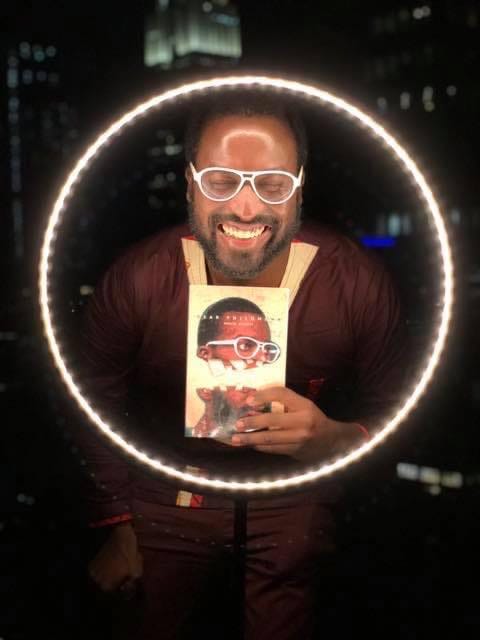

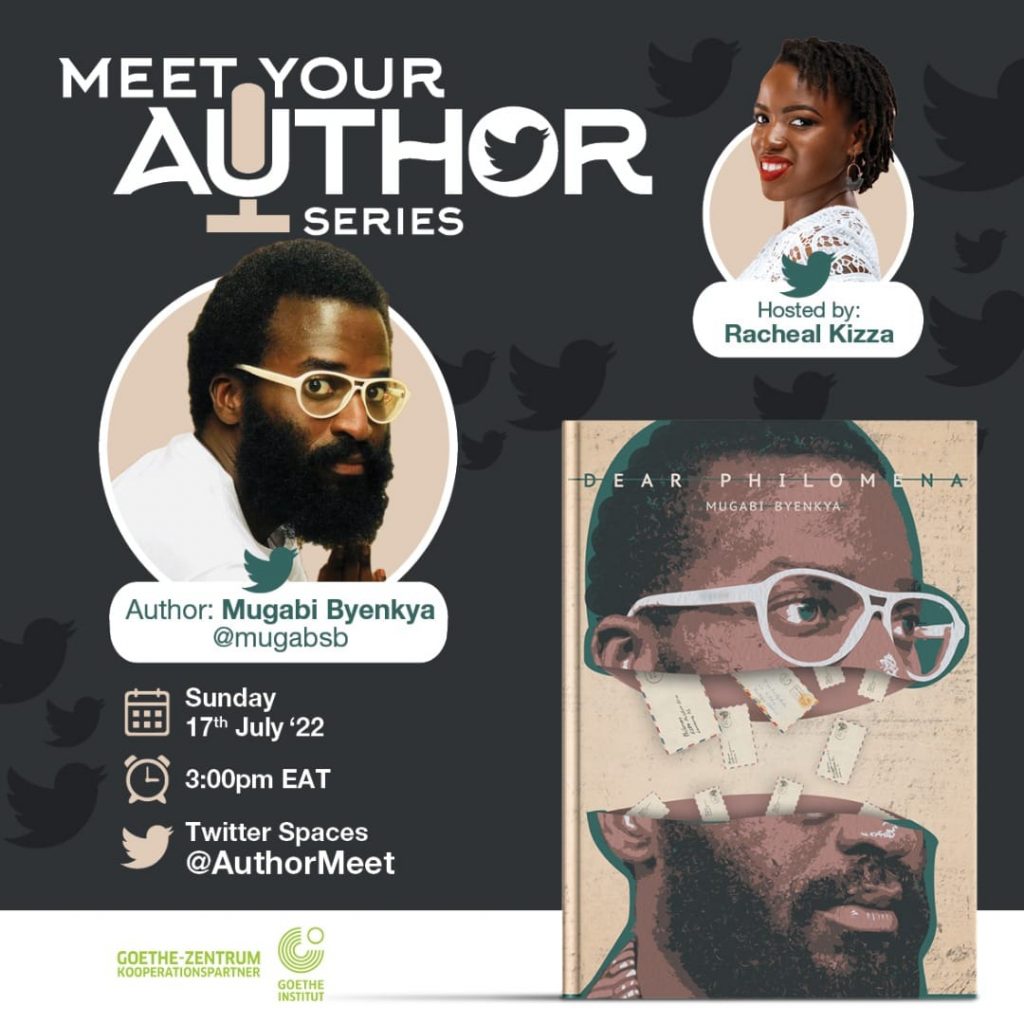

Mugabi Byenkya is an award-winning writer, poet and occasional rapper. His writing is used to teach High School English in Kampala and Toronto schools. He won the Discovering Diversity Poetry Contest in 2017.

In the same year, his award-nominated debut, ‘Dear Philomena,’ was published and he went on a 43 city, 5 country North America/East Africa tour. In 2018, Mugabi was named one of 56 writers who has contributed to his native Uganda’s literary heritage in the 56 years since independence by Writivism. Dear Philomena (Discovering Diversity Publishing, 2017) was named a Ugandan bestseller in the same year.

I hosted Mugabi in conversation on Twitter Spaces earlier this year and we spoke about his book, chronic pain, support and racism in healthcare.

Racheal Kizza (Racheal): Congratulations upon publishing Dear Philomena. Why did you choose to tell your story the way you did in Dear Philomena?

Mugabi Byenkya (Mugabi): Thank you for the congratulations! I chose to tell my story in an epistolary text messaging form (with occasional diary entries, flashbacks, social media posts and a more conventional prose prologue and epilogue) because that was what was accessible for me to write. As a result of surviving three strokes and the subsequent health complications I manage, I can only handle so much text processing in a day. This is even more limited when it comes to creative writing. For example, when I was writing “Dear Philomena,” I would write for 30 minutes and the exertion that 30 minutes of writing entailed on my body, would induce an excruciatingly painful and exhausting several hours long seizure. This would leave me incapable of writing for the next day or two or three.

I needed a form of writing that was accessible to my disabled body and more importantly, I wanted a form of writing that was able to be read by disabled people like me who have issues with text processing, by people who’s first language is not English (which includes the majority of my family) and by neurodivergent people like myself who find it difficult or impossible to engage with large blocks of text. The book was designed with accessibility in mind for both me the writer, and the reader, whomever they may be.

Racheal: Let`s talk about your struggles with suicidal thoughts, depression, seizures and strokes. What effects have they had on you and what adjustments have you had to make over the years?

Mugabi: This is a multifaceted question so I’m going to answer it one by one. In regards to my struggles with suicidal ideation, the struggles are still present, but my therapist taught me healthier coping mechanisms for how to deal with suicidal ideation. I’ve also attempted suicide once, which I discuss in the book, and what that attempt taught me was that I didn’t actually want to die, I just wanted to escape the pain. I’ve yet to find a way of escaping the pain outside of sleep (which I’m eternally grateful for, as the first couple of months after my strokes, the pain manifested in my sleep and I’d have vivid nightmares that I was being mauled alive by wolves, or other forms of excruciating pain), but I can distract myself from the pain by keeping my mind and body occupied through: a regular sleep routine thanks to new medication that works wonders; listening to music (I’m listening to music as I write this); listening to podcasts; reading comics; watching TV or movies; engaging in daily physical therapy exercises; sticking to and having a regular daily routine; keeping myself occupied through working on projects and the administrative side of my writing career (booking and doing interviews such as this one, submitting writing to publications, shooting my shot at residencies and grants, answering emails, engaging with social media etc.); meditation; catch up calls with friends and family; and respecting my bodies harsh limits, not pushing past them but resting when my body needs to.

Similarly, I manage my depression in a similar way, as I’ve noticed that my depression gets worse when my health gets worse, so prioritizing my health and maintaining whatever baseline I have is of the utmost priority. This may mean I’m not able to immediately get back to DMs or emails as I operate on crip time and get around to things when I’m able to, I’m no longer pushing or forcing my body to operate in the capitalistic mindset that demands immediate responses. I was on anti-depressants for five years which helped with my depression but like most anti-depressants, they stopped being as effective after five years of taking them, so I weaned myself off them and now manage depression through the same above list that I use to manage my suicidal ideation. I’d encourage anyone who uses anti-depressants to manage their depression to continue doing so, as they worked wonders for me for five years, and I only stopped them once they lost efficacy and I had other tools to help manage my depression.

In regards to my seizures, these have had a massive effect on me and forced me to drop out of the Master’s programme I was in at the time, and rendered me unable of pursuing full-time work due to the harsh limitations they place on my body. They are incredibly frustrating to deal with, and I’ve gone months- years largely bedridden as a result of the combination of the seizures, my chronic pain and my chronic fatigue, as I discuss in “Dear Philomena,”. I’ve had to make numerous adjustments to my life, namely limiting the amount of mental, physical or social exertion I do in a day, so as to minimize my seizures. I’m on a new medication now which helps suppress my seizures, but I still have a maximum amount of exertion that I can take before I start spasming. If I continue it leads to a full-blown seizure, so I have to limit my activity and work within my limits. My seizures have led to me having to quit full-time employment, having to cancel several shows on my book tour, having to cancel writing deals that I had and having to deal with the fear from friends and family of my seizures. It’s been a tumultuous past eight years dealing with them as best I can, but at my worst, they shut my body down for months at a time, I lose my ability to process text, I’m rendered largely bedridden and go into a semi-conscious state. So, I’m grateful to have them under better control now, as it has been far worse in the past.

My strokes have had the largest impact on me. The first stroke when I was 9 years old, completely paralyzed the right side of my body (which was the dominant side of my body), forcing me to have to re-learn how to do everything from eating to brushing my teeth, to writing with my left hand. It also shifted me from the former able-bodied privilege that I enjoyed to the marginalization that comes with being disabled. Plenty of adjustments had to be made, from taking me out of school for a term as the doctors attempted to stabilize my condition and ruled out the fatal causes of childhood strokes, they suspected I had. To the intensive physical therapy, I had for the next nine years, to being banned from P.E. for a year as my body could not handle strenuous physical exertion, so I would go to the library and read books. To the ableism I internalized from my family, friends and physical therapists who all set the goal (either consciously or subconsciously) to try and get me to pass as able-bodied as possible. I faced bullying because of my disabilities throughout my schooling, and I’m forever grateful to the people who stood up for me against the bullies. The first stroke also gave me a migraine disorder and photophobia, and the well-intended but ultimately destructive belief that I could power through anything.

My second and third strokes, broke me and my power through anything mentality, as powering through led to excruciatingly painful and exhausting seizures. They gave me: a chronic pain disorder that feels like my body is on fire 24/7 and being crushed simultaneously, that only goes away when I sleep; a chronic headache that only goes away when I sleep; a chronic fatigue disorder that renders me weak and tired all the time and the aforementioned seizure disorder. As I said earlier, I had to drop out of my Master’s programme as a result of the second and third strokes, move in with my sister and attempt to recover but I was never able to recover the abilities that I had at 22. I’ve come to accept that over the past 8 years and come to modify and work within my limitations instead of pushing myself to my own detriment, as so many doctors wrongly advised me to do. I used to tie a lot of my self-worth to my work and being unemployed for so long after my strokes was a difficult adjustment, but I’ve come to realize that I’m worth more than my work, worth than my productivity, worth more than conventional measures of intelligence and worth more than what capitalism tells me. I also managed to create a successful writing career for myself, as a consequence of my former employment options no longer being accessible to me and for that I’m grateful. I’d still rather not deal with the pain, seizures and fatigue, but the experiences that adapting to my limitations have brought me (writing “Dear Philomena,”; being my own booking agent, publicist and manager; going on tour; receiving messages from people who my work has resonated with; having my work discussed in book clubs and classrooms in Kampala, Nairobi, Bahrain and Toronto; receiving fellowships and awards for my writing; achieving the lifelong dream of a 4-year-old Mugabi who proudly proclaimed “I want to be an author when I grow up”), I’m grateful for as I likely would not have these experiences, as young as I did, without my strokes.

Racheal: Compassion care is core to the book. Let`s look at it from two dimensions. Self-care: “My therapist made me realize how I look at myself and I did not like what I saw at all. So I`m loving myself more. Small steps!’’ How important is self-care to you as you go through this journey and to men generally? We have seen self-care categorized for women but nothing much has been said for men.

Mugabi: I think self-care is very important regardless of gender and is very important to me personally. The late Mac Miller has a song titled “Self Care” about self-care and Kendrick Lamar has a song called “i” that is an anthem of self-love. So, I don’t think these discussions are not being had among men, but I’m averse to categorising things within the gender binary. There is so much more beyond cis-gendered men and cis-gendered women, and these marginalized gender identities are often the ones most deserving of self-care and self-love, because of the societal forces that actively work to oppress them. Self-care and self-love are very important to me personally, as it keeps me going on difficult days and allows me to refresh and recharge once I have hit my maximum capacity. I spent the past two years largely bedridden due to deteriorating health, but thanks to everything that my therapist taught me and my healthy coping mechanisms, I was able to cope with all the stresses this entailed, far better than I did after my second and third strokes and had to spend a couple of months largely bedridden. This is a testament to the power of self-care and self-love.

Racheal: In the book, Mugabi has support from family and friends but is frustrated by friends who make his sickness about them. They want him to move on swiftly, get out of his head, etc. How important is support from family and friends? How can they be helped to support a sick friend/relative?

Mugabi: I get asked this question about my frustrations towards my friends frequently, and I often don’t understand where it’s coming from. I have every right to be frustrated over people who are centring themselves over my illness, people who want me to move on swiftly when I physically can’t, or people who want me to get out of my head, acting like my illnesses are not real or valid. Support from family and friends saved my life, so I think it’s of the utmost importance. If I hadn’t had my sister to take me in, I could have easily ended up homeless. While I was working in D.C. after the events of the book, I worked as a stylist with a non-profit called Suited For Change that offered professional clothing for free to women to wear on job interviews, and for the job if they got it. While talking to a lot of the women, I found we had incredibly similar stories, the difference is, they didn’t have a sister to take them in when they got sick and ended up homeless. Beyond the housing support, my sister along with all the friends and family I mentioned in the acknowledgements of “Dear Philomena,” offered a lot of emotional support while I was: struggling with my pain and seizures; receiving conflicting information from the doctors and unable to do all the things I used to be able to and loved to do.

During this time, I reached out to plenty of friends for support, and quite a few dropped the ball, but the ones who stepped up, I’ll forever be grateful as they validated me, listened to me vent, and were righteously angry on my behalf. The character Philomena is modelled after several real-life friends I have, who I would not have survived that year without and to who I am eternally grateful.

I think family/friends who are looking for ways to support a sick relative should read my book as Philomena serves as an amazing model for a supportive friend, but more importantly should be present, validate the emotions the person is going through, avoid toxic positivity, listen and make an effort to check in on the person. A lot of people are scared of sick people and don’t visit, I know this very well from first-hand experience, so the people that do check in either virtually or physically, always means a lot.

Racheal: In the book, Mugabi joins a support group for chronic pain and it soothes him. He is validated. How important is support from people who can relate to your hardships?

Mugabi: The chronic pain support group I joined was revolutionary as it was the first time, I had met so many people who also managed chronic pain. Granted, they all managed different types of chronic pain and the majority were not limited in the ways I was. Nonetheless, I’ll always be incredibly grateful to that group and later the Pain Rehabilitation Clinic I attended, and later Disability Twitter and Brianne Benness’ No End In Sight, for showing me that I’m not alone. It’s so easy to feel alone when you’re experiencing hardships, which is why I think it’s invaluable to have a support community who are experiencing similar hardships, who can relate, who can commiserate and who can understand in a way that the most well-intentioned family or friend will never be able to. It also helps to talk shop and find ways to manage your hardships that have worked for others who have actually experienced the hardship, rather than well-meaning friends suggesting I go vegan or try yoga without realizing that I have already tried those options, and they were ineffective for me. There’s no one size fits all approach for anyone going through hardship and people who can relate get that.

Racheal: Dr.Lumeya brings up the issue of witchcraft when it comes to Mugabi`s health struggles. Does that mirror your experience since in Uganda most people think witchcraft is what causes mental illness and unknown or unexplained health struggles?

Mugabi: Yes, this mirrors my experiences in Uganda since my first stroke at 9 years old and mirrors what my amazing therapist (who Dr. Lumeya is based on) asked me because he understood the cultural context that I came from. I’ve had people tell me I’m cursed and that the causes of my disabilities were witchcraft since I was 9 years old, I’m 30. What do you think the effect is of being called cursed for 21 years (the majority of your life)? I’ve been taken to the faith healers, to the witchdoctors etc. until I was old enough to say no and no longer be dragged along to all these swindlers, who take money from desperate people. Witchcraft is so commonly used as an excuse to either not accept something that you don’t want to or to not accept that you don’t know everything and doctors don’t know everything. I go into this in detail in Brianne Benness’s No End In Sight Podcast, but in summary: “all these people, no matter how well-meaning they might be, they’re throwing all these things at us, but are they paying for them? Are they facilitating the process? Do any of these people who are throwing all these witch doctors at me ever come to visit me? Ever come to check up on me? No.”

Racheal: Let`s talk about able-bodied privilege as you reference in the book. Briefly explain the concept.

Mugabi: “Able-bodied privilege is the unearned advantages based on the values of the dominant able-bodied society that we live in. Sometimes able-bodied people perceive themselves as ”normal,” and wrongly presume that everyone has the same opportunities, abilities and access. They can look online to check out new job opportunities; a person with vision impairment cannot. They can get in our car and trek to the mall; an individual in a wheelchair needs wheelchair-accessible transportation to make that trip. They are able to listen to the radio; others may need listening devices to do the same.

Able-bodied privilege may also mean that someone might invite a group of friends to a quaint restaurant that doesn’t have ramps or elevators, thereby ostracizing one friend who needs those accommodations to join the group. For many people, the world is set up for easy access. People with disabilities do not have the same ease of access, but that is often forgotten by the rest of society. Similar to but not the same as male privilege, white privilege, cisgender privilege, heterosexual privilege, educated privilege, class privilege, Christian privilege etc. The fact that so many people are unaware of the able-bodied privilege they have, and I’m asked this question so frequently, is a testament to how often disabled people like me are neglected by society at large. (Source: https://study.com/academy/lesson/what-is-able-bodied-privilege-definition-examples.html)

Racheal: In the book, you talk at length about racism in health care. Mugabi experiences it in subtle ways when doctors dismiss him, misdiagnose him or are lazy in their diagnosis. Talk to us about that.

Mugabi: Doctors have been dismissing, misdiagnosing and being lazy in their diagnosis of me since I was nine years old. Doctors are trained by medical school to operate from a checklist, which works great in simple acute cases but works terribly in complicated chronic cases like mine. Not to mention, the fact that doctors are overworked, so they often don’t even have the time to familiarize themselves with my lengthy health history, everything I’ve tried and what they could offer that would be different. Medical school and the position of being a doctor breed a certain level of arrogance that does not like to be told you are wrong. Or that a patient understands the lived experience of an illness way better than a doctor ever will from a textbook. I have a strong healthy animosity towards doctors because they have been treating me like a fascinating medical mystery, instead of as a human being since I was nine years old.

Doctors’ objective is to get you in and out as quickly as possible, so they can see another patient and make more money. Doctors lack empathy, care and compassion, which should be fundamental traits of the profession. Add racism on top of that and all the white doctors I saw in the states assumed I was a drug seeker, looking to get high off opiates because I am Black. The few Black doctors I saw in the states (of which there are far too few) were more compassionate and willing to explore more options. This does not however absolve all Black doctors, as the Ugandan doctors I’ve seen have all dismissed me as too complicated, like I said earlier, they don’t want to deal with anything that doesn’t fit in their neat little checklist.

Racheal: Tell us about getting the book published. What was the process like?

Mugabi: I had been actively telling people I was working on a book through social media and personal interactions, so I was able to speak it into existence in a sense. While I was working on edits, my brother’s housemate (at the time) older brother walked in and asked what I was working on. I told him I was working on edits for my book and he responded by saying his wife knew a publisher. I was able to get the publisher’s (Discovering Diversity Publishing) contact details and we got along great and were able to work out a deal where I own all the rights and can do with it what I want worldwide. However, I had to fund the initial print run through an incredibly successful Kickstarter campaign (for which I’m forever grateful to my supportive community for donating to). I value the full ownership that I have over my work, as it was able to yield far better returns than your standard royalty agreement, and I was able to pay for the costs of my book tours through book sales, t-shirt sales and performance fees. The process was fairly standard once I read through the contract, we started copyediting, working on design, and working on typesetting. I had the wonderful cover done by the talented Mawa Amer, then I had the initial proofs sent which I went through with a fine-tooth comb and had some changes done until the final proofs came in that I was satisfied with and then the book was published. I was then able to find a printer in Uganda (because I had full ownership) to print a Ugandan edition at a more accessible rate, which recently sold out!

Racheal: What projects are you currently working on?

Mugabi: I’m currently working on three secret projects which should be out by the end of the year, but I’m keeping a secret. One thing I learnt from the rollout of “Dear Philomena,” was that being so public about the writing process helped in terms of accountability, but it also led to a lot of beating myself up over not being able to write, when people were DMing me asking why I hadn’t posted a word count, because I had a seizure and was unable to write. I’m trying to have a healthier relationship with my body this time around, and not beat myself up over my body’s limitations but instead work within them. Also, a lot of people during the editing process were not respectful of my artistic process, and were harassing me asking what was taking so long, and why I hadn’t finished the book yet. I will never put out work that I’m not happy with, and my health and other responsibilities do not allow me to work on my projects on a daily basis. I don’t want to go through what I did with “Dear Philomena,” with entitled people demanding I put the book out when I knew it was not ready, so I shall be keeping my three projects a secret until they are ready.

Racheal: How is your health now?

Mugabi: My health has improved since the events of the book. I was on a boom/bust cycle from 2016-2022. I would push myself, then crash hard for days, weeks, months or even years. It’s only recently that I was able to spend over a month at a hospital in Thailand, where I dealt with all the usual frustrations from doctors that I mentioned before, but was able to discover a medication that suppresses my seizures, a new physical therapy regimen that helps me manage my pain and fatigue and the power of pacing. Now I’m no longer trying to push myself to hold down a 40-hour work week like all those doctors wrongly told me to. Now I settle at 4-5 hours of work every weekday and maybe another 4-8 on the weekend. I stop when my body starts spasming, telling me I’ve hit my limit for the day. I don’t push myself. I settle and I’m at peace.

Ultimately, by doing a little bit each day, I’m able to do a lot more sustainably. I’m no longer having several month/year-long flares and my seizures are infrequent and moderate in comparison to the daily violent seizures, I used to face. My pain is still there but doesn’t spike as high as it used to, my fatigue is still there, but not as severe as it used to be, and I’m able to do the things I love once more. I’m able to work at my own pace, earn a little something from it, prioritize my health and ultimately work within my body’s limitations, instead of against them.

Follow Mugabi on Twitter, Instagram and the website.

Buy Dear Philemona from Mahiri books (East Africa), North America and Kindle.

Your article gave me a lot of inspiration, I hope you can explain your point of view in more detail, because I have some doubts, thank you.

You’ve done a marvelous job with this article. It’s clear, concise, and very informative. Thanks for sharing!

This is one of the most comprehensive and engaging articles I’ve read on this topic. Great job!

Your insights on this topic are really valuable. Thanks for providing a fresh perspective!